That led to the current project with the working title of High-Bounty Men and High-Number Regiments: A Reappraisal. I started out with two components to the reappraisal. First, it seemed to me that the bounties in 1862 may have been high enough to be economically attractive--that the volunteers of 1862 were not necessarily purely motivated by patriotism as historians have traditionally claimed. Second, the actual performance of the "high-bounty" men and "high-number" regiments in battle needed to be examined to test the poor soldier accusation.

I decided that the best way to pursue the first component was to look at how much money men in various civilian occupations made in 1862 and compare that to how much money they would make if they volunteered. Bounties were the largest component of military compensation. The federal bounty was a constant, but the state--and especially the local bounties--varied significantly. I set out to research local bounties, in the end documenting the bounties for over one thousand communities in the Eastern States. I concluded that volunteering could have been "economically compelling" in 1862 for men in lower-paying occupations like laborer.

In 2018, Earl Hess put me in touch with William Marvel, who was then about to publish

Lincoln's Mercenaries. My "income-based" approach complements his "wealth-based" approach to economic motivation and we both agreed that Civil War historians traditionally gave too little attention to the economic aspect of motivation in the early years of the war.

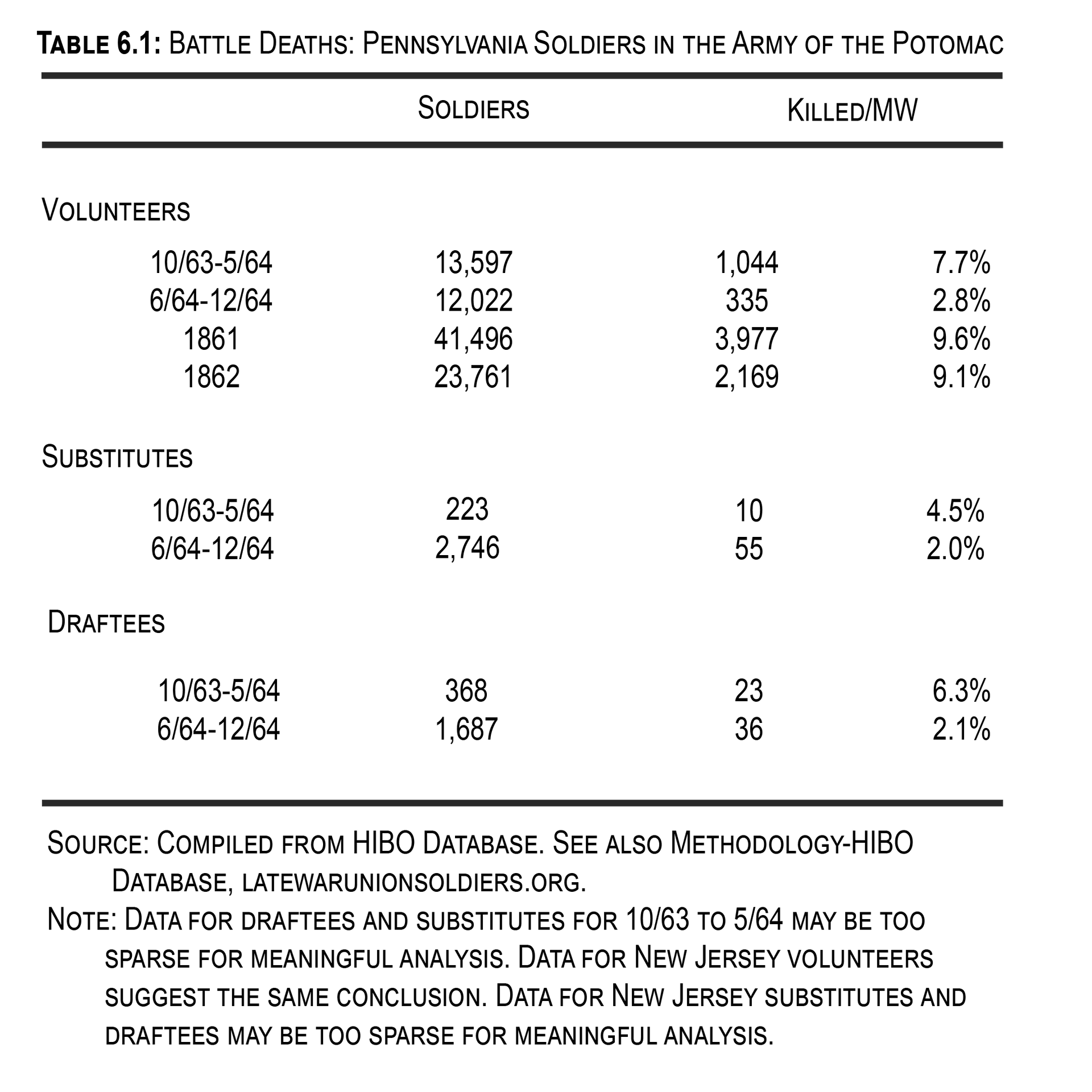

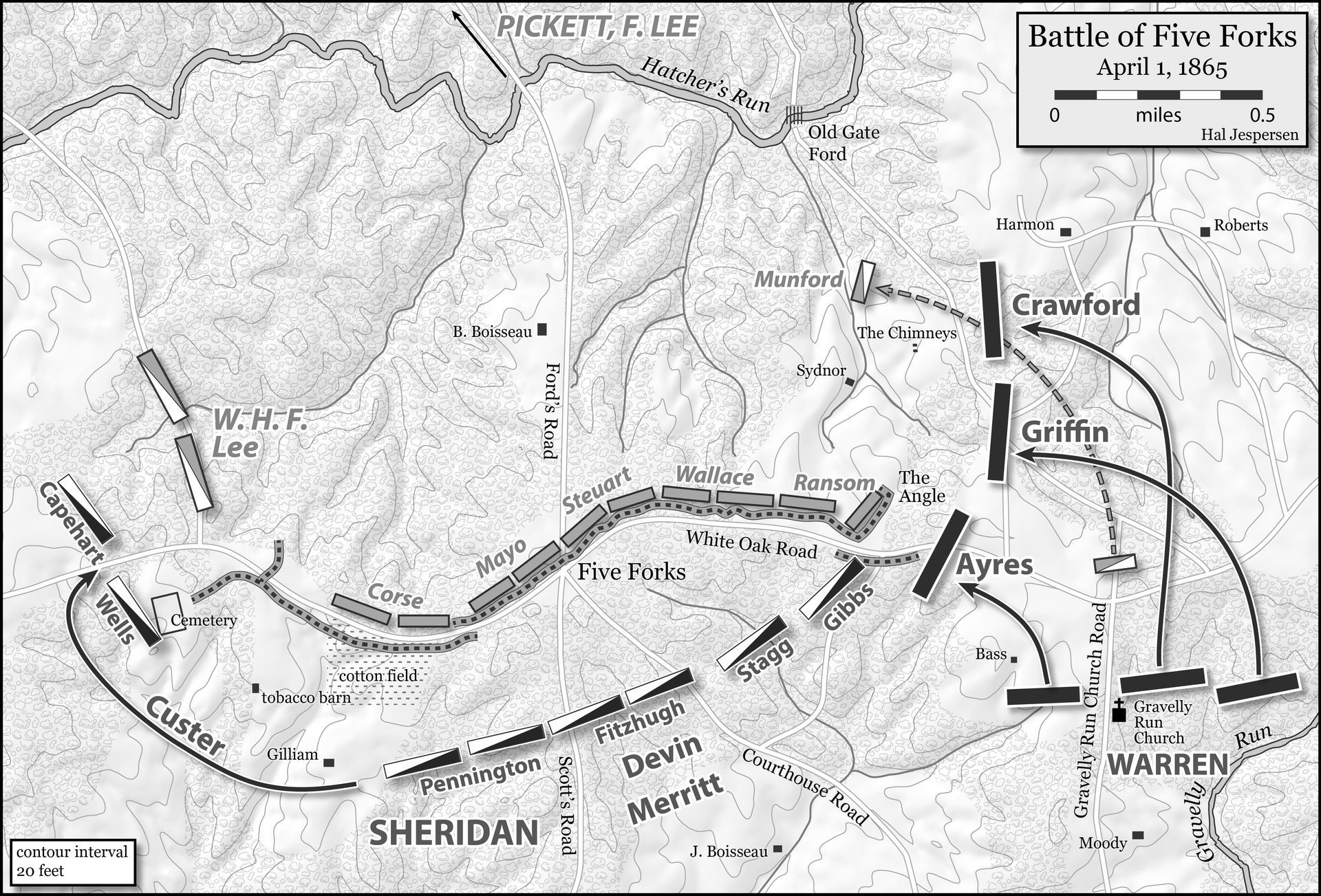

My "income-based" model definitely indicated that the vast majority of "high-bounty" men could have been motivated by the money to enlist, but that does not ipso facto mean that they made poor soldiers. I began looking for examples beyond the 179th New York of how "high-bounty" men and "high-number" regiments actually performed in battle. Early on, I encountered the six "high-number" regiments in Hartranft's Division of the Ninth Corps, who were widely praised for "performing like veterans" in their first battle when they shut down the Confederate breakthrough at Fort Stedman. The "high-number" 185th New York and 198th Pennsylvania, which comprised Chamberlain's Brigade in the Fifth Corps, received similar praise during the Five Forks Campaign.

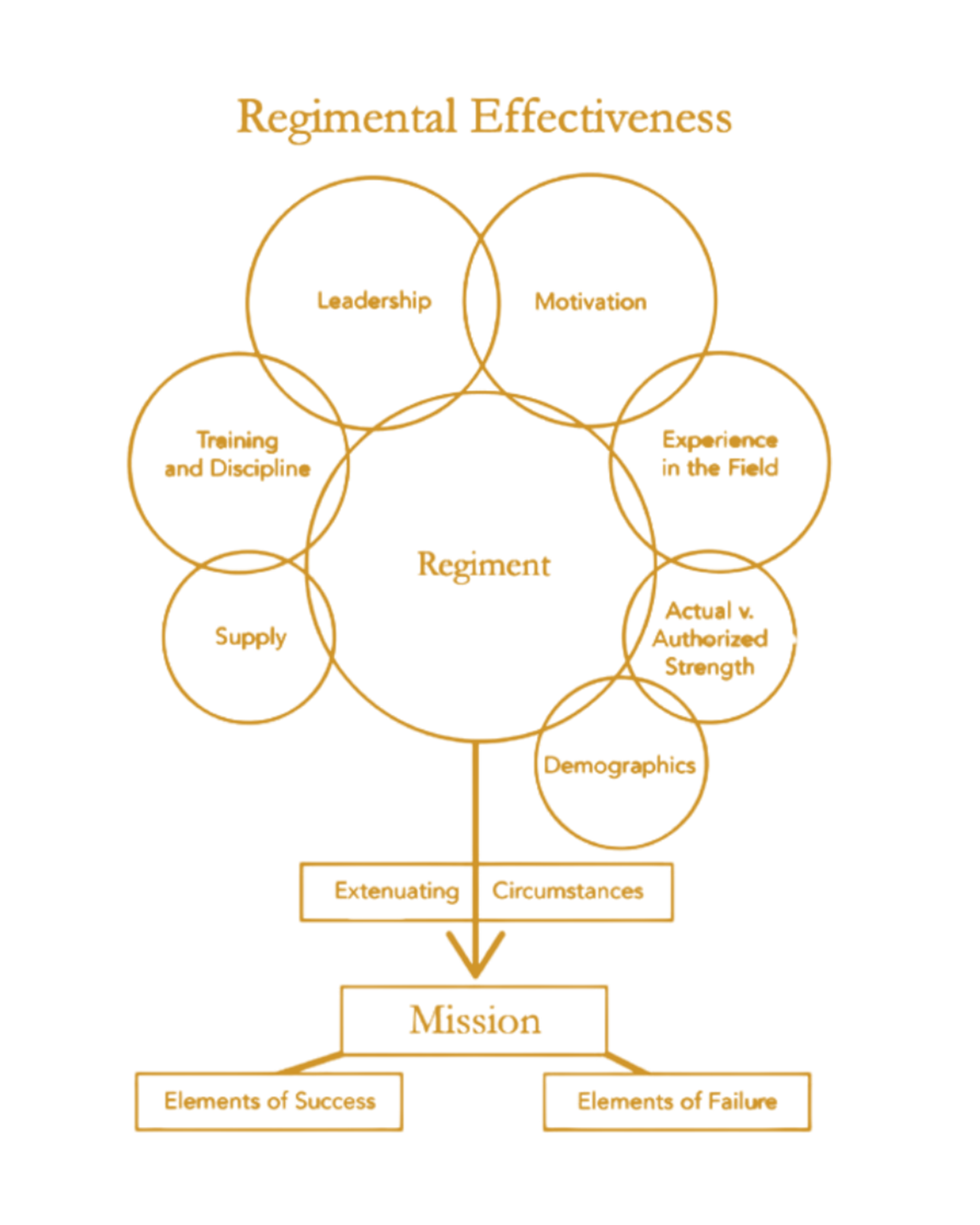

A natural question arose. How was it that the "high-bounty" men were able to perform like veterans in their first battle. In order to answer that question, I initially drew on my army training as an intelligence analyst, which taught me how to identify and analyze the capabilities of military units. I combined my military training with the combat effectiveness methodology of historians like John Lynn (The Bayonets of the Republic) and the readiness methodology used by the Department of Defense to create the Regimental Effectiveness methodology that I followed for

High-Bounty Men in the Army of the Potomac. The heart of the book is Chapter Six, which explains the methodology, and Ten and Eleven, which apply it to the "high-number" regiments in Hartranft's Division and Chamberlain's Brigade, respectively.

The late Richard J. Sommers' claim in

Richmond Redeemed that the "high-bounty" men had "wrecked" the Second Corps at the Battle of Second Reams's Station was one of the most damning accusations against the "high-bounty" men that I had encountered. There is no dispute that the Second Corps was badly defeated at Second Ream's Station, but my research-- which included a detailed analysis of the composition of the regiments engaged--showed that the veterans from 1861 and 1862 were subject to just as much criticism as the "high-bounty" recruits. Mistakes by the Union commanders, including General Hancock himself, also contributed to the Union defeat. (See Chapter Nine)

I certainly do not claim that the "high-bounty" men made perfect soldiers or that they were better soldiers than the veterans of 1861 and 1862, but as a group, the "high-bounty" men in the Army of the Potomac definitely were not "poor" soldiers as historians have claimed for far too long. The "high-bounty" men in the Army of the Potomac made good soldiers and they are entitled to share in the glory of the Union victory.